It was two days before VE Day, 80 years ago. Hitler had taken his own life a week earlier. The war in Europe was, in effect, over. Allied troops were being repatriated to their home countries. One such journey began that morning from Mourmelon-le-Grand, 93 miles north-east of Paris.

There were 30 souls on board: five crew members and 25 “litter” patients. “Litter” in this context refers to patients on stretchers, due to the nature of their injuries. Contrary to what some might assume, not all those on board were American; two were British.

The aircraft was a Curtiss C-46D, an American military transport plane. It was bound for RAF Greenham Common, near Reading in Berkshire, and was scheduled to continue to the United States the following day.

Harold William Atkinson Findlay was one of the two British servicemen on the flight. He had been a prisoner of war since 1940. In early 1945, as Russian forces advanced, the Germans – unwilling to allow Soviet troops to liberate the POW camps – began marching prisoners west. This forced movement is known by several names: “The Black March”, “The Long Trek”, “The Long Walk”, and “The Great March West”. Around 80,000 prisoners endured the ordeal, which at times stretched to 1,000 miles. An estimated 3,500 perished in the -25°C conditions – the harshest winter of the century in that region.

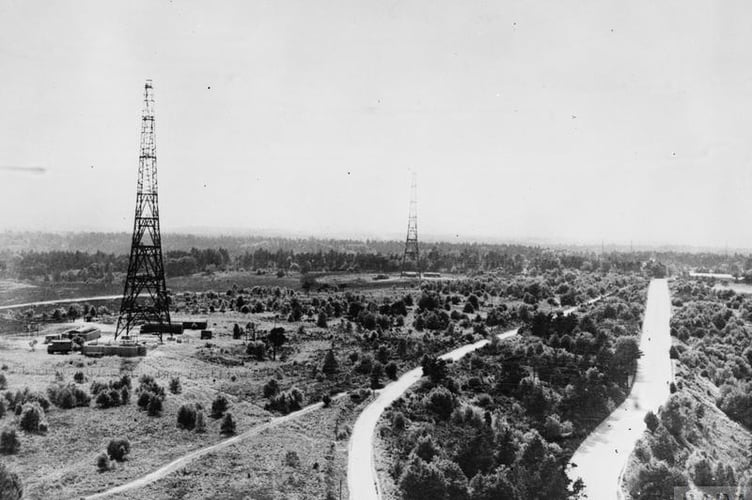

The RAF station at Gibbet Hill was part of a network of communication bases across southern and eastern England. The station comprised four 250ft-high wooden masts that transmitted precisely timed radio “pings” to assist Allied bombers over occupied Europe. This so-called “GEE” system (G for Grid) served two purposes: to improve bombing accuracy, which had often been poor in the war’s early years, and to guide aircraft safely home.

The weather on that day in May was atypical. The cloud base was low. The pilot, flying visually rather than by instruments, dipped in and out of the cloud layer at around 600 feet near Churt to maintain sight of the ground. As the aircraft approached Hindhead, the ground began to rise. The pilot gained altitude and avoided the terrain and trees, but clipped one of the masts. The right wing was torn off, and the aircraft crashed in flames, killing everyone on board.

Also among the dead was the Station Commander at RAF Hindhead, Flight Lieutenant Emerson Parish, a Canadian. Knowing that the war was effectively over, he had sent the rest of his shift to celebrate at a local pub. His act of generosity and selflessness spared further loss of life – had they remained on duty, the death toll could have been closer to 40.

One can imagine Findlay’s parents waiting at RAF Greenham Common to collect him and take him home for tea – the family lived in Reading. But alas, it was not to be. After surviving unimaginable hardship, he perished on home soil, just miles from safety and those who loved him.

By Andy Jones

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.